The most popular movie of 1970 was Airport, a star-studded disaster film, and the biopic Patton was the most honored film at the Oscars, but to me the most interesting movies that came out that year, in terms of understanding the time, are Woodstock, Beneath the Planet of the Apes, and Joe. The first movie, Woodstock, is the most well-known, a concert film that presented the hippie subculture for public consumption. The Age of Aquarius was also near the center of the Peter Boyle vehicle Joe, which follows the story of a reactionary proto-Archie Bunker blue collar worker who turns into a hunter of hippies. As for Beneath the Planet of the Apes: it was about a horrific world in its last thrashing moments before complete annihilation. A disturbing toxic landfill of a movie, Beneath fell well short of the critical and popular success of its predecessor, Planet of the Apes, but somehow with its disfigured mutants and atomic terror and narrative disorientation it manages to offer an acute portrait of the spiraling uneasiness of that first year of the decade, which saw the breakup of the Beatles, the deaths of Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin, and the Kent State Massacre. In 1970, the world felt a little shaky to everyone.

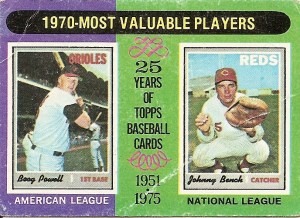

In 1970 I was still a few years away from balancing uncertainty and nightmares with a worship of baseball players, but if I had been old enough I would have taken comfort in the rocklike solidity of Boog Powell and Johnny Bench. I did take solace in both of those individuals anyway by the mid-1970s, when I started buying cards, in part because a bit of their history came to me in this card celebrating their 1970 MVP awards. They had been around for a while by the time I came along, and this felt good. There was gravity in their names. Boog. Bench. They made the world seem sturdy, durable.

Years later, when I was a young man, I watched Beneath the Planet of the Apes for the first time, on video, then stepped out onto the seventeenth story balcony of the apartment where I’d watched the movie and felt a powerful wave of vertigo. The movie, which ends with the white light of atomic bombs, had tapped into some deep insecurities I’d always had about the essential flimsiness of life, and the balcony seemed small and unsafe, though in truth at that moment I would have felt unsafe anywhere.

The moment of panic abated but never fully disappeared, not really. When I was a kid I had an inherent belief that the world was well-made and ably steered by adults who knew what they were doing. Now that I’m an adult I know all too well the potential for mistakes in everything.

It extends everywhere, even to the world of greatest solidity, my baseball cards. Take this card for the 1970 MVPs. Did they even deserve the MVP awards? In the American League, Powell had very good year, but it was decidedly less productive offensively than that of Carl Yastrzemski, and Yaz even stole some bases that year and aided his team by being flexible and splitting his estimable fielding skills between left field and first base as the team needed. Over in the National League, Bench finished behind Orlando Cepeda and Tony Perez in slugging percentage and was not among the top ten in on-base percentage. (Bench was arguably the greatest fielding catcher who ever lived, which coupled with his significant offensive production lends legitimacy to his award, but the stat-heads among us might think that his glovework and leadership did not entirely make up for a tenth-place league finish in adjusted OPS.)

Anyway, my unease in the world, my adultness, even my vague understanding of “adjusted OPS,” has its repercussions. I’m a tentative, cautious cipher. Sometimes in the morning I say something to myself that’s vaguely related to a prayer. I wonder if something unusual and amazing will happen during the day. It feels as if it never does. Each day for me is sealed shut somehow. Within the confines of it I have my pleasures, and even once in a while experience something like joy, but is there ever the sense of shattering newness?

I think I used to be closer to a kind of life that would let in the strange light I seem to be lacking. When you’re younger, you stumble into adventures. The truth is, I don’t want adventures. I don’t want to have to rescue someone from a building or invite an unshowered wino to sleep on my couch. I barely even want to have a conversation with anyone. I like my bubble. Leave me alone.

But still, there’s that wondering about newness. It’s partly a request for it and partly a request that it stays away. The train I ride travels along the highway for a while, and yesterday it came to a station stop right next a woman crying inside a car stopped on the shoulder beside the passing lane, the front of the car caved in. I don’t want that kind of newness. But it’s coming. One way or another, it’s coming. This bubble will burst.

I first started writing about this card a couple months ago, believe it or not, after hearing Boog Powell mentioned during a radio broadcast of the Phillies’ pennant-clinching win over the Dodgers. Chase Utley, the Phillies second baseman, had tied with Boog Powell for the record of consecutive playoff games in which he had gotten on base. Utley then got on base in the first game of the World Series and now has the record all to himself, which means we’ll all have less of a chance of hearing the name Boog Powell as we go about our daily rounds.

I for one was glad to hear the name. I always have been, ever since I first read it on a baseball card, the newness of it sending a thrill through my body, a message that new things are OK, that everything will be OK, that the world yet to come will be—ah, you know what? I probably didn’t think any of those things, not really. I’m just trying to reach for something literary and elevated before trudging off through the snow to a train that I hope doesn’t derail. But it’s true: the name Boog did once comfort and thrill me. Still does, just a little. Boog.

You must be logged in to post a comment.