The Indo-European root of the word euphoria seems as if it could also be the root of the word Berra. It’s bher. According to my American Heritage Dictionary, it means “to carry; also to bear children.” On October 8, 1956, the player shown here was being carried within Carmen Berra, who was attending a baseball game. The conclusion of this game offered up the template for baseball’s most resonant entry into the language of euphoria. The game was one of those rare instances in which the win itself is so staggering that it doesn’t seem to count until men are leaping on one another.

I’ve watched the end of this game and its aftermath several times. The pitcher, Don Larsen, perhaps still in the state of deep trance that allowed him to suddenly upend a relatively nondescript career with stunning brilliance, with perfection, shows little reaction at the moment of victory. After the final out, he takes two steps toward his dugout and then, as if sensing and wanting to avoid the maelstrom swelling up around him, begins to break into a slow loping jog.

Fortunately, Larsen’s catcher is up to the unique demands of the moment. After bouncing out of his crouch, he quickly motions with both hands, like a conductor or a choreographer, as if he’s trying to direct Larsen to follow the miraculous illogic of the moment and start floating. As he continues bounding toward Larsen he senses that his pitcher will not be capable of the unprecedented manner of rejoicing required, so he’s the one who leaves the earth.

We do this sometimes. We don’t stay up forever. We fly into one another arms.

We are carried.

***

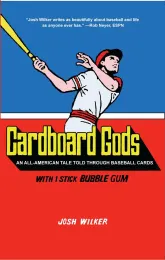

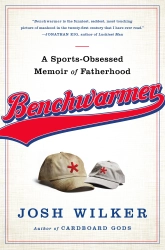

No son can ever be free of the ghost of his father. Consider this 1980 card featuring a confident, handsome young man ready to take on life on his own terms. The back of his card lists a number 1 draft pick distinction alongside some promising minor league stats, but these intimations of future glory are crowded out by a large, artless cartoon sporting the obvious information connecting the young man to his father, who in addition to catching the only perfect game in World Series history and then creating with his leap into Don Larsen’s arms the template for baseball euphoria was also the winningest, most beloved player in major league history.

Dale Berra was himself a World Champion at the time this card came out, the recipient of a full share in the Pittsburgh Pirates’ 1979 World Series prize money despite being a September call-up who arrived to the team too late to be eligible for postseason play. In fact he was barred from even sitting on the Pirates bench in the playoffs. In the remaining seasons of his decent but unspectacular 11-year career, he wouldn’t get anywhere near a title again. Like the rest of us, he’d never get the chance to catch the final out of a season and leap into a pile of roaring euphoria.

***

My six-year-old and I sit side by side sometimes and yell and laugh and curse and bring one another back to life. We hold devices in our hands that allow us to control the movements of two cartoonish avatars of presumably Italian descent with mustaches not altogether dissimilar to the one worn by the young man shown here.

“Pop me out of a bubble!” my son squeals. And I jump up and free him and together we go on. But really it’s much more often that he’s freeing me. He has a knack for staying alive. I die easy, again and again, and because he’s alive I get to go on.

I thought about the two of us sitting side by side and playing and laughing tonight as I was sifting through the online traces of Dale Berra. Right up at the top of the Google pile for Dale Berra is an ad he’s in for Atari back in the mid-1980s, just when that kind of virtual living and dying was starting to take hold in the world. In the ad Dale Berra’s electronic altar ego, a hungry circle, is ceased by a ghost.

***

Dale Berra’s father was, among other things, a mediocre major league manager, at least by the measure of his lifetime record, in which his failures slightly outnumbered his wins. His final major league win as a manager brought his lifetime record to 292 wins and 293 losses. He went on to lose three more games before, as often happened with people in his position, i.e., the manager of the New York Yankees, he was abruptly fired. That final managerial success by Dale Berra’s father was surely heightened by the contributions of Dale Berra himself, who that year had become only the second player in major league history, after Connie Mack’s son, to play for his father in a major league game. Dale went 2 for 4 at bat and started a key double play in the field.

That was in 1985. Later that season another lasting association would get attached to Dale Berra’s name when he admitted to cocaine usage while he’d been a member of the Pittsburgh Pirates. From then on, schmucks such as me with blogs and Twitter feeds and all the other ways in which to disseminate our shallow associations would think Dale Berra? 1. Yogi’s son. 2. Cocaine.

He tried it first as a very young man at a New Year’s Eve party to kick off 1979, a year that would crest with his team at the very top of the world. He liked the feeling. Who wouldn’t?

“It made me feel euphoric,” he explained.

***

My father was a brilliant student and scholar. I heard this from the friends he made in the 1950s and 1960s.

“We were all in awe of him,” his friend Marty said.

He had grown up very poor during the depression. His family had to suffer when his own father was unable to find work. The lack of work itself seemed to eat most deeply at my grandfather, who eventually took his own life, leaving my father without a father before he’d reached his teenage years. Who can say what burdens this puts on a person? All I know is that there were a couple of times along the way when my father came to a fork in the road, and down one road was a life of scholarship and financial uncertainty, and down the other road was a steady job. I believe the last of these forks came with the arrival of my older brother. My father had been in graduate school at NYU, but he stopped short of earning his masters, instead focusing on working full-time to support his new family.

Many years later, after he retired from a long and useful career as a sociological researcher for various state and city agencies, he used his NYU alumni status to get a card that allowed him entry to the NYU library on the south side of Washington Square Park. The card included a certain number of guest passes.

One day we went to the library together. I was gathering information for a young adult biography I was writing about Confucius. My father was researching whatever he was interested in, probably something having to do with Marxism or World Systems Theory. We sat at a table by a window several stories above Washington Square Park, both of us with tall stacks of books beside us, both of us silent, both of us reading. We were up above the trees, side by side, trying to understand, trying to know. We were both very much alive, and as long as I’m able to carry the memory we always will be.

***

The person I’m most drawn toward in the clip of the final pitch and ensuing celebration of Don Larsen’s perfect game is not Larsen or Dale Berra’s father but a figure who disappears almost as soon as the clip starts. It’s the pinch-hitter, who stands there for a moment in disbelief as the pitch is called a strike. It’s a somewhat famously blown call, but it was decided in that instant and forever after that we won’t really care so much about that. But the pinch-hitter does. He looks befuddled. The moment is famous for perfection, for joy, but life is not defined by those things. Life is for us most often what it is for the man at the plate whose name, according to an interview with Dale Berra by the baseball historian Bob Hurte, would be seized on by Yogi Berra’s wife, Carmen Berra, at that moment as just right for the child she was carrying.

Dale Mitchell checks his swing and, knowing the truth of the pitch he’s just let go by, turns toward the authority behind him, the ump, as if to appeal to him, but it’s too late. It’s just the same as if there’s no one there at all to look to, to beseech, to implore. And then this Dale is gone from the clip, leaving behind for the player on the card at the top of this page his name, to be joined with the other much more famous name from that moment, a preposterous combination, as if to be human is to be suspended in a thin bubble in midair somewhere between euphoria and knowing.

You must be logged in to post a comment.