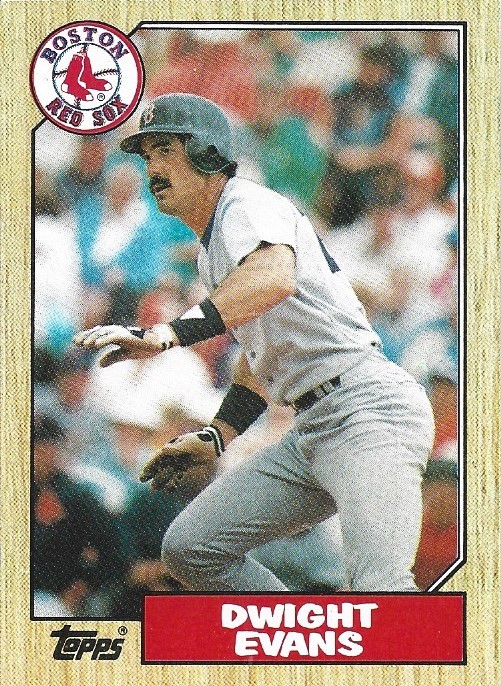

I believe that in this 1987 baseball card Dewey Evans has been captured in a split second of hope. An instant earlier he had been in the low, coiled stance he’d begun using halfway through his career, and then he saw a pitch in the zone and swung and connected and is captured here just after his bat has flown from his hands. His eyes suggest that he’s hit the ball in the air, but not too high. A hard line drive has cleared the infield and is on a sizzling path toward . . . what? A gap? A wall? A sprinting outfielder’s glove? Hope at its core is not flowery, not a greeting card notion. It’s a sharp in-breath, a want for life.

***

My older son turned thirteen recently. I found myself thinking back on the moment I first laid eyes on him. He came out on his back, covered in blood and amniotic fluid and crying and still connected by umbilical cord to his mother, who had been through the worst ordeal I’d ever seen anyone go through with my own eyes, and I was flooded with relief that the hours of white-hot suffering for my wife were over, and I was staggered with unspeakable shock and joy at the arrival of the shut-eyed squirming bloody tiny human in front of me in the hospital lights. My whole life shifted at that moment to him, with hope.

***

Here are some things I’m hoping for: I hope to finish a novel I’ve been working on for the last several years. I hope I can manage the stress I have in the job I do to make a living. I hope most of all for my two sons to be OK and to have happy, full lives. Sometimes when the stress of my job is peaking, I hit the narcotic pipe of the quitting fantasy, but this would leave us without income or insurance, eventually without shelter or food. Obviously I need to work. So I work and because of the world we live in now I work at home and so work and home are the same and so I trudge upstairs at the end of yet another in an endless string of inconclusive battles against the regenerating undefeatable beast of stressful tasks and there I am with my family, my face grim, my posture hunched, my eyes bloodshot and exhausted. It can’t be an accident that my sons seem stressed out too. I am now so removed from my own childhood that I am wide open to inaccurate renderings of it, and so to say I don’t think I was as stressed out as they were is a very dubious claim. I did have night terrors, I know that, and that was fucking awful. But day to day I think I did OK, especially in the summer, when I could go buy baseball cards and fool around with imaginary games out in the yard and driveway. It’s a different world for my boys. They live in a city and don’t roam around like I did living in the country. They’re inside a lot. Their freedom happens virtually, in a game where the object is to shoot everyone. They play with their friends, connected via headphones, and I hear laughing and squeals of excitement, if not joy, though the younger of my sons also gets frustrated sometimes and starts screaming, and then the older one’s stress starts spiking, and it is just the fucking worst, everyone against everyone in a house of never-ending stress.

***

As a fan you assume that the greatest feeling you’ll ever get is when your team wins it all, and that’s true, but in terms of sheer intensity I wonder if an even more powerful rush is in those slim moments of ferocious new hope when your team seems doomed but somehow, astoundingly, survives. For me, because of where I grew up and who I looked to for hope, examples of those moments are all from Boston teams. The Hendersons, Dave in Game 5 of the 1986 ALCS, Gerald in Game 2 of the 1984 NBA Finals; Dave Roberts and Bill Mueller and Big Papi in Game 4 of the 2004 ALCS; the famous Game 6 1975 World Series home runs, first Bernie Carbo and then Carlton Fisk, and in between those two miracles, yet another: in the 11th inning, Joe Morgan smashes a line drive to deep right, the Reds’ Ken Griffey taking off from first, and Dewey Evans sprints straight back toward the wall in desperate pursuit.

In that moment, as in all of them, the internal monologue of the fan is the same.

We’re dead, we’re dead, we’re dead . . .

We’re alive!

***

I believe that in this 1987 baseball card Dewey Evans has just released his bat. It’s a moment that was a long time coming in the progression of baseball cards in my collection. My life, or at least the part when I started being able to remember, began with baseball cards, and Dewey Evans was always there, and he was always, except for the last year in which I heavily collected cards, holding a bat. In his 1975 card, from when I was seven and first starting to collect cards and root for the Red Sox, Dewey is holding a bat, a posed shot. He strikes a similar bat-holding pose in his 1976 card. His 1977 card also shows him holding bat, this time in a game and from the side, showing him staring out at the pitcher and in the upright batting stance he used before he started remaking himself as a hitter under the demanding eye of hitting guru Walt Hriniak. In his 1978 card he’s back to a posed shot, his bat again perched over his right shoulder. In 1979, another posed shot, the bat is still there, now resting on his shoulder. In 1980, finally, no bat is included in his photo, and his expression as he looks off to the side is as if something has been taken away from him.

All of the photos on these cards that came to me throughout the years I was collecting are absent of the three things that came to define Dewey Evans: the leather version of the fielding equipment that helped him win eight gold versions of that equipment for being among the three best outfielders in the American League in a given year; his crouching batting stance, implemented during the second half of his career as he transformed into the most productive slugger in the 1980s in the American League; and his Magnum P.I. mustache, which appeared with the gravitas of something that had always been there right around the time he made the career turn from streak-hitting defensive whiz to an abiding, majestic presence with the all-around talent and bearing—to use the hagiographic parlance of old-time sportswriting—of an immortal. One who shall live forever!

As my childhood gave way to teenage years and then to the first lurching years of adulthood, Dewey Evans was still there, year after year, still firing lasers from right field, still settling with magisterial deliberateness into his coiled stance, the toe of his bent front leg just barely touching the dirt. The narrative of baseball immortality never quite took hold for him, and as yet he still hasn’t been called for induction into the baseball Hall of Fame. I don’t think I’m the first person to wonder what might have been if his career had been flipped, his best years first. That’s how Jim Rice’s career unfolded, and he’s in the Hall of Fame in part, I think, because of the superstar aura he laid claim to in his earliest seasons. Evans played in Rice’s shadow (and to varying degrees in the shadow of the legendary Yaz, the golden Lynn, the heroic Fisk, and the robotically indomitable Boggs), but he proved over the course of his career to be Rice’s equal as a slugger and better than Rice at getting on base and better than almost everyone who ever played the game at fielding his position.

According to a great new book by Evans and his co-writer Erik Sherman, Dewey, Evans isn’t bitter about not yet gaining entry into the Hall of Fame. He’s taking it in stride. This is in line with the portrait that comes across in the book: here’s a man who is not going to spend much time agonizing about the things he can’t control. He’s come by this wisdom through great resolve and an abiding faith, having persevered through personal trials far beyond anything that can happen on or related to a baseball field. On the back of the 1987 card at the top of this page, Evans’s long line of statistics allows for just one sentence of text at the bottom: “Dwight and his wife have 2 sons and a daughter.” That line, as it turns out, points to the heart of the new autobiography, which intermingles Evans’s baseball memories with stories of being a parent. It’s clear that being a father has been the most important part of his life, and that his greatest joys have been in spending time with his family and seeing his children grow and find connections and joy in the world. Though Evans and his family had to face enormous challenges, as both of his sons were born with neurofibromatosis, a serious medical issue that required frequent hospitalization and surgeries, it’s clear that this was never allowed to define their lives. First and foremost, there was hope, there was love.

***

The Red Sox lived to play another game in the 1975 World Series, which they lost. Dewey Evans, still at the outset of his career and surrounded by superstars, figured there would be many more. But hopes kept rising and falling every year, and it wasn’t until 1986 that Evans got another chance to win the World Series. Until reading Dewey, I’d never associated the most famous play of that 1986 World Series with Evans, with his perspective. It’s Game 6 again, just like in 1975, but this time instead of a deep line drive that a young Evans is able to run down, saving hope, the action in the right-field domain of an aging veteran is one of powerless irrelevance. A ground ball skids through the infield, through Bill Buckner’s legs, and as the opposition mobs the winning run at home plate in ecstasy—We’re alive!—the ball rolls toward Dwight Evans and comes to a stop.

***

Dewey is a book about love and hope. Evans’s love for the game comes through, and his love for his teammates, and most of all his love for his family. After reading about how proud Evans was to catch his friend Bill Buckner’s ceremonial first pitch on opening day in 2008, I rewatched that moment and wept, thinking about Bill Buckner, gone now, and thinking about Dewey, white-haired but still looking strong, beaming with pride for his friend. Dewey had been there all through my life, a constant presence, a pillar of hope. Childhood fell away, and Tiant left, and Fisk left, and Lynn left, and Jim Ed faded, but Dewey was still out there. There’s hope!

I only ever weep when thinking about old greats. I only ever weep in gratitude.

I watched the clip at the end of a long day of work. When it was over I wiped my face on my shirt, closed up my computer, and went upstairs to find my sons.

You must be logged in to post a comment.