Bill Bene

June 20, 2012(This post originally appeared on The Classical.)

Harold

I can’t find any information on the internet about Bill Bene’s sentencing, if it has even happened yet. The latest news, that Bene pled guilty and faces up to eight years in prison and hundreds of thousands of dollars in fines, appeared in late March of this year. I don’t know what’s happened to him since then.

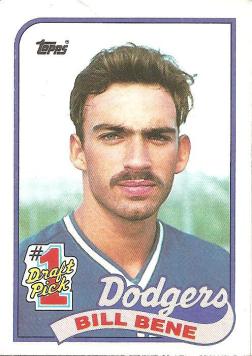

If there are still going to be court proceedings in conjunction with Bill Bene’s sentencing, I want to believe that Harold will be brought in as a character witness. The defendant surely will have aged from his appearance in a 1989 Topps card, but Harold will be essentially unchanged after all these years, albeit maybe a little scuffed in places. Maybe his souvenir stand Los Angeles Dodgers batting helmet will be slightly askew.

***

“I fooled them for a while,” Bill Bene said.

This was in 1988, a month before the major league draft. Bene was admitting to a reporter from the Los Angeles Times that his high school career, spent exclusively as an outfielder, had been iffy. He’d known the best he could ever do was bluff and hope.

“I was never a very good hitter,” he said. “I guess I was meant to pitch.”

I guess.

Last week I discovered the 1989 Topps offering featuring Bill Bene in a friend’s box of unwanted cards. I’d never heard of him. A number 1 draft pick? This guy?

I’ve been discovering bits and pieces of Bill Bene ever since. Yesterday I watched a bird thump head-first into one of my windows.

“Jesus,” I said.

“Happens a lot,” my wife said. “We need to put up some stickers.”

It’s a big picture window. The birds are just flying along and wham.

“God, imagine what that’s like,” I said, pitying birds.

But then I thought about it some more. We can only ever guess. Every single step. And sooner or later we’ll smack into something. We’ll be stopped.

***

A couple of years ago, my wife and I drove to St. Paul, Minnesota, to attend a booksellers conference. My memoir was due out in a few months. The publisher sprang for gas money and a hotel room for us. The hope was that giving away bound galleys to conference attendees would drum up some buzz for the book. At the conference, hysteria for my book did not ensue. I wasn’t expecting it to, but even so the concrete affirmation that my book was just another book among hundreds of books, thousands of books, dampened my impulse to engage in fantasies of impossible deliverance. And who even reads anymore anyway? It wasn’t like I’d made a movie or, perhaps even better, a video game. It was great to have a book coming out, the realization of a lifelong dream. But it wouldn’t change anything. I would still be fastened to my life.

Afterward, my wife and I had a couple of drinks at the hotel bar, where a karaoke night was in session. There were maybe twenty people scattered around the bar, watching one another take a turn at the mike. On Words Without Borders, Jean Harris, reviewing Dubravka Ugresic’s Karaoke Culture, ponders the karaoke singer.

The hallmark of karaoke culture is a preference for faux versions of real things. So why does this world have a large population that opts for the theme park version every time? Because, according to Ugresic, “the very foundation of karaoke culture lies in the parading of the anonymous ego with the help of simulation games.” The denizen of karaoke culture is a cipher addicted to dreaming he’s somebody else: the one whose assertion of ego actually gets him somewhere.

***

Back when I was a kid I used to fantasize about being discovered. It started modestly, when my older brother was in little league. As I watched his games I imagined that a foul ball would bound my way, and I’d scoop it up and fire it back onto the field, wowing everyone with the strength and accuracy of my arm. (I hadn’t yet seen The Bad News Bears, where Kelly Leak’s superpowers as a baseball player are first announced in just this way.) As the years went on, this fantasy of being discovered got more preposterous, until eventually it involved a limousine pulling up at the edge of our driveway as I was throwing a tennis ball at the duct tape strike zone on the garage door. The backseat window would come down, revealing Carl Yastrzemski’s melancholy features creased into a smile.

“Quite an arm, son,” he would say. He’d produce a major league contract, holding it out the window toward me. “It’s just what we need.”

This is a deep American dream: to be discovered. To be seen, truly, and to be told with certainty, beyond any guesswork, that at our core we are aglow. That we have a great gift.

Absurd as it sounds, this is more or less what happened to Bill Bene. Bene was fumbling through the usual descent through baseball that all but the tiniest portion of the population experience, the game becoming harder and harder until it ejects us entirely out of active participation and into passive fandom. For me this occurred when I was fourteen and struggling in Babe Ruth league play. Bill Bene’s expiration date as a baseball player was set for when his passage as a guess-hitting high school outfielder concluded.

Instead, former major leaguer Randy Moffitt noticed Bill Bene had a strong arm and suggested he try pitching. According to a conflicting version of the story, this suggestion was made by Randy Moffitt’s father, Bill; what is indisputable is that Bene was blessed by the divine intervention of a close family member of Billie Jean Moffitt, Bill’s daughter and Randy’s sister, who gained renown beyond even that of my imagined fairy godmother, Yaz, under her married name, Billie Jean King. Billie Jean’s relation pointed the coach at Cal State-Los Angeles toward Bene, and it was at that institution, on a pitcher’s mound, that he would be discovered.

He first took the mound for his college team in 1986. From the beginning, he threw very hard and yet with so much wildness as to be nearly useless to the team. Scouts began to appear, more and more all the time, drawn to his promise, ignoring his flaws, much in the way one falls in love.

His complete college stats are displayed in full on the back of his 1989 “#1 Draft Pick” card. They are not good, as shown most succinctly by a career ERA of 5.62. And there aren’t even any positively suggestive “hidden” numbers below that broad-brush metric. He did not strike out more than a batter an inning, for example. Worse, he walked more batters than he struck out. Still, the scouts swarmed.

“We had 55 scouts at one game,” Bene’s college coach, John Herbold, said, adding for the sake of comedic hyperbole, “and we had so many radar guns going at the same time there was a power shortage.”

Somewhere along the line the fluttery hyperbole surrounding Bene began to coagulate into something more solid. By 1988, Los Angeles Dodgers general manager Fred Claire, who by the estimation of awards-givers at the end of that year would be deemed the keenest executive in all of major league baseball, was saying that Bill Bene had the “best arm of any prospect in the country.”

The Dodgers selected him with the fifth overall pick of the 1988 draft. In the minors, he continued to struggle. The temptation, with this “#1 Draft Pick” card in hand, is to imagine his story as a tragic fall, but where was he falling from? He wasn’t like David Clyde, who’d soared unbeatably through high school baseball, a national sensation, only to smack into an invisible barrier upon his immediate promotion to the major leagues. Bene’s nearly instantaneous ascension to the top of baseball had never been anything but an illusion.

***

I don’t participate in karaoke nights, but I sing sometimes. I once spent a year in a cabin in the woods. Because I had no electricity I had no entertainment beyond what I could cook up myself. I played my acoustic guitar and sang all the time. I wasn’t singing to heaven. I was lonely, going nuts. I hoped that someone might hear me singing and would be drawn to the sound. A woman, specifically. She’d appear from out of the birch trees, a smile creasing her melancholy features.

“Quite a voice,” this beautiful illusion would say. “It’s just what I need.”

If I discovered anything in my year in the woods it was that there’s only one discovery available. There’s no word for it, no voice to sing it.

***

A year or two into Bene’s professional career, he was so wild that he was demoted to remedial instruction outside of official action. In a simulated game, where the only other participant was a teammate standing in the batter’s box, a pitch got away from Bene, unsurprisingly, and broke the wrist of the teammate. The coaches further modified Bene’s remediation, replacing the human batter’s box attendant with a department store mannequin.

Bene drew a mustache on the mannequin. He named it Harold.

His pitching briefly seemed to improve, but this was an illusion. His minor league numbers tell the demoralizing story that sometimes people can’t change. We can dream of being discovered, of being told we have a great gift, and this dream might even come true, but eventually a second discovery will overtake the first. This latter discovery is the one we pray to avoid: our home in the world has been secured erroneously, and in that home we are a fraud, and upon the discovery of our fundamental insufficiency we are cast out.

***

This weekend I was reading an FBI document. It had an ad at the back, an attachment provided to illustrate the case being made that AOL be ordered to turn over all email records for a user with the email address dansternsplace@aol.com. This email address appears in the ad, the only contact info provided for the seller of the product being advertised, which is a hard drive containing 120,000 “Top Quality Karaoke Songs.” According to some information included earlier in the report, the price for this hard drive, $299, is far below the market value for the songs, which are all protected by a copyright that the seller of the product does not have a claim to. In addition to mapping the particulars of the felony of copyright piracy, the document sets out in painstaking detail the failure to pay taxes on any of the dubious earnings. Piracy, tax evasion: the subject of the report was in big trouble. The ad at the back serves as a disjointedly cheerful epilogue that somehow makes everything even bleaker. “Makes a great gift!” the ad copy exclaims.

From 1997, when his minor league career ended, until the appearance online of this 2010 FBI report, the internet does not contain any traces of Bill Bene save for some occasional, inevitable mockery embedded in his inclusion in periodic “biggest draft bust” retrospectives. After 1997, Bill Bene became for a time invisible, anonymous, at least in terms of overt internet traces. At some point he created what was in essence an online avatar, “Dan Stern,” and through that alias made hundreds of thousands of dollars by faking fakery.

I find myself imagining the courtroom. The prosecution will play the music of the victimized karaoke corporations, each song hollowed out by design, a vacuum in the center of it to pull in that hidden part of us that wants to be discovered. In the quiet following these empty songs the defense will turn to Harold. They will adjust his limbs accordingly and prop him in the witness stand. Gaze unwavering, mustache intact. His expression will be the same as it was in those early days, not long after the dreamed-of discovery had been made and before the other discoveries had fully overtaken and obliterated the first. No matter what question Harold is asked, his answer will be the same. He will sing. No one will hear. Life is flight until we strike this invisible song.

I work at Cal State LA, and from my office window–if I turn my neck just right–I can see the diamond off in the distance; I also walk by it a couple of times a week. And, since you posted this piece Josh, every time I see the field I think of Bill Bene and the possibilities of youth.